Pin

Pin

Nicholas Ireland, a father of two, teaches humanities to middle schoolers at a classical school in Alabama. On this episode of the podcast, he tackles the subject of poetry.

Why is poetry important? What poems should I start with? What makes good poetry good? What if I don’t understand poetry? What questions should I ask my kids when we talk about the poems we read? Nicholas answers all these questions and more, plus gives us enough recommendations to keep us busy reading excellent poems for a long, long time. Enjoy!

Pam: This is Your Morning Basket, where we help you bring truth, goodness and beauty to your homeschool day. Hi everyone, and welcome to episode 8 of the podcast. I’m Pam Barnhill, your host, and I’m so happy that you’re joining me today. Well today we get to talk about one of my absolute favorite subjects on the show, but I realized that poetry is not something that everyone enjoys and actually, I hope that we’re here to change all of that today. I think one of the number one reasons that many people don’t like poetry is because they’re intimidated by it, or actually, they’re intimidated by the way they were taught about poetry in their educational experiences. So maybe we can move past that today with some of the tips that we have on the podcast. So sit back and I hope you enjoy and maybe come away with a new view of poetry and how you can share it with your children. Nicholas Ireland is a graduate of the University of Tennessee where he studied humanities and philosophy. Now, he spends his time teaching humanities to 8th grade boys at Providence Christian School in Alabama where he lives with his wife, Melissa, and his two adorable little boys. Last spring at our local homeschool conference he led a session all about diving into poetry with your kids and all the homeschool moms were raving about this one. He’s joining us today to share about how we can incorporate great poetry into our Morning Times without fear. Nicholas, welcome to the program.

<p>Nicholas: Thank you, glad to be here.<br />

Pam: Let’s talk a little bit about the importance of poetry. If I’m a homeschool mom and maybe poetry isn’t my thing, why is it important to do poetry with my children?<br />

Nicholas: If you’re a parent trying to educate your child in the Scriptures, first of all, if that’s important to you, and that was the first thing I thought about, so much of God’s Word is communicated through poetry. The very first words that man ever spoke were poetry; they said, “At last, this is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” and so that’s a starting point for me is, there is something innate to our being human where we want to express things and as song or as poetry where it could be expressed through prose and a lot can be expressed through prose but we seem to have this desire to use our language differently and to use the kind of things that are found in poetry that give expression to who we are and what we’re feeling and what we’re experiencing.<br />

Pam: Cindy Rollins says that poetry forces us to think metaphorically, and I think that’s a very interesting concept that it causes us to think differently than how we normally think.<br />

Nicholas: Sometimes westerners get so caught up in, and certainly as a logic teacher teaching categorical logic (this is this, and truth values and making statements) but not all truth is that way, there’s a lot of analogical truth as well and we understand a lot of things through analogy and I think that’s part of who we are as human beings.<br />

Pam: Having that great exposure to poetry really helps us to see things in analogies better by having that repeated exposure.<br />

Nicholas: And think about how often God communicates to us in that same way and communicates himself to us in that same way. It’s really striking when you think about. How many analogies Christ himself uses or is throughout the Scriptures (God is a rock- that’s not a categorical truth, he’s not a rock, but he communicates himself to us in that way and since so many others).<br />

Pam: Why do you think it is that poetry intimidates some people?<br />

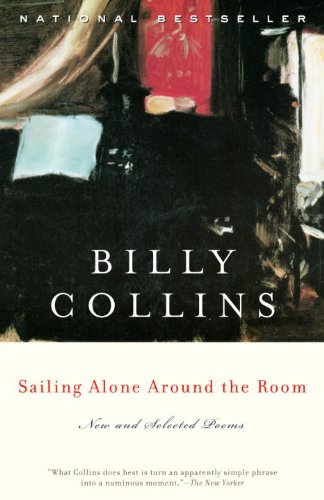

Nicholas: We have to be able to understand it to be able to enjoy it, and that’s certainly true with poetry if we have time, I would certainly read this short poem by Billy Collins called Introduction to Poetry and I will recommend and do recommend it to folks. It’s in his collection of poems called Sailing Alone Around the Room. He just talks about how he can’t get his students to read a poem and just let their minds wander through it and just let it be a part of them. He can’t get his students to play with it. All they want to do is find out what it really means. I think poetry is pretty dense stuff and heady stuff. And if people are approaching with this necessity of ‘I have to really understand it and master it’ I think most people just aren’t going to do it.<br />

Pam: So you think it’s this tension that we have within ourselves when faced with a poem that, for some reason, we have to get to the deeper meaning in it and we can’t just sit back and enjoy it?<br />

Nicholas: I’ll speak for myself and that was certainly true of me. Even as an English major I was well out of college before I think I really started enjoying poetry. I read it a lot and there was a lot that I liked about it but in terms of picking up an anthology or a picking up a collection and just really sitting down and enjoying some poetry for the evening was not something I did much until into my 20’s.<br />

Pam: So, what was it that made the difference for you? What was the turning point that allowed you to overcome that intimidation and start enjoying it more?<br />

Nicholas: Well, I know one was just an experience with certain poets that did that to me. One of those would be Gerard Manley Hopkins who I read a little bit of in college and enjoyed but it wasn’t until I came back to a poem or two of his and a friend maybe was just engaging with that poem when I was at summer camp as a counselor and I just saw him really delighting that poem and I thought ‘there must be something here’ and to this day when I read Hopkins it’s one of the most pleasurable things that I do. It’s certainly one of the most pleasurable things that I read. A modern day poet, a contemporary poet named Luci Shaw is one who has had a similar effect on me and I would say she mimics or channels Hopkins quite a bit in her poetry. Just realizing that I could sit down with their poetry and then branching out from there, the way we all do with music, “Oh I like this musician,” sort of a Pandora model, people like this- they’re similar in some ways- but then you branch out more and more.<br />

Pam: We need a Pandora for poetry; that would awesome.<br />

Nicholas: That would be great. We’ll work on the Poem G-nome project, and I would add to that Billy Collins as well, I think Billy Collins, for me, he’s not everyone’s favorite and in academia I don’t think he’s anyone’s favorite but I think he’s a wonderful poet who can really make poetry a lot of fun and I think he’s pretty insightful. Reading and finding a couple of poets that you just happen to enjoy can be a bridge to a whole bunch of others that you can also enjoy.<br />

Pam: Searching for that one, and I’m sure that there’s one out there for everybody who’s going to give a spark that you’re just going to really fall into and really, really like. Well, let’s talk a little bit about poetry with your children because I think this is probably a great way for a lot of moms who have not found poetry horribly approachable in the past would be to start looking at some poems that are aimed at or geared towards their children a little bit and they can start enjoying those. I know that I was really not aware of say, Robert Louis Stevenson from my own childhood for whatever reason and in just reading him with my children and seeing their delight in him I’ve started to take more delight in his poems. We read his about the blocks today and it was such a delightful little piece and something that they totally understood. So using those poems that are aimed a little bit more towards children I think is a great way for some parents to get their feet wet in a non-intimidating way. Let’s talk a little bit about how you can share poetry with your children at home.<br />

Nicholas: I’m going to butcher C. S. Lewis here who said, in reference to children’s literature, I think you’ve heard the quote that literature that’s fit only to be read by children is not fit to be read at all.<br />

Pam: Yes! No, you didn’t butcher that one.<br />

Nicholas: I do feel similarly about poetry. I think you find those greats, like Robert Louis Stevenson, Lewis Carroll- guys who are really, really thoughtful artists and authors and thinkers, first and foremost, who then write poetry. It was like even in the world of fiction or music I’d rather read or listen to an artist who is a Christian than a Christian artist, same thing with novels and things. Maybe it’s a slight nuance; it seems to play out in a much less subtle way. I think there is a big difference between those poems and books for that matter that are written solely for children, aimed at children, and I tend to stay away from those even though I really like Shel Silverstein when I was growing up, he’s not my go to guy right now for when I’m recommending poetry to kids, when I’m reading poetry with my own kids. I think it’s important for them to hear excellent writing and to be exposed to what is excellent. I think it’s important to find those good poets who also happen to resonate with children.<br />

Pam: So, let’s help everybody out. Give me a few people that you would really recommend.<br />

Nicholas: Well, I mentioned a couple: Lewis Caroll has several that are great for kids to read. Ogden Nash is hilarious.<br />

Pam: Yes he is.<br />

Nicholas: And a lot of his are shorter and about animals and just his rhymes. [**inaudible** 9:53] really off the wall are great. If your kids can handle just a little bit of off-color language his poem The Common Cold is avarice, it’s one of my favorites. Rudyard Kipling I think writes good poetry, the kids can resonate with, and that seems I’m leaving a couple out.<br />

Pam: We actually happen to be big Hilaire Belloc fans around here, I don’t know if you’ve read very much of his stuff.<br />

Nicholas: No, that’s someone I’m not familiar with.<br />

Pam: The Yak is one of his and The Vulture is another one. Those are some that we really enjoy; another animal guy.<br />

Nicholas: I don’t know how many others he has that resonate well but Robert Service who wrote, The Cremation of Sam McGee. I think ballads like that are great. Longfellow and his ballads, because again you get The Midnight Rider of Paul Revere and things like that. Starting at a fairly young age they enjoy the story behind those poems and they’re so well written and then I would just actually recommend one ballad that I’ve found really, really useful is called A Child’s Anthology of Poetry. The one I have is by Ecco Press. I think the compiler, if I’m not mistaken, the editor is Elizabeth Sword, so that’s a book that I’ve found really useful when I taught 5th grade, it was great. I’d just turn them loose with that sometime, a kid who just had some spare time and say, “Just flip through and find a poem that you like in here and let’s talk about why you like it and we’ll read it in front of the class.” And then when I was working with my 7th graders a couple of years ago in an English class most of the poems I picked were out of there and the poems are far from childish but many of them are really great for children.<br />

Pam: What are some techniques a mom might use in helping her kids get familiar with poetry? You’ve mentioned handing an anthology over to a child and letting them find one. What are some other things we could do?<br />

Nicholas: Well, I’m assuming they’re going to be sitting down enjoying the poem with them, that’s a given, and so I think just reading through poems with them. I was amazed the other day, I was reading an article from the Circe Institute about getting your children to love reading, I hadn’t read much of the article and there was a hyperlink to “because of this video” and I thought, ‘This is going to be some great videos from Circe Institute’ and I click it and it’s a three year old reciting a poem by Billy Collins called, Litany, which is a really great poem. It was really funny to hear this three year old reciting it, but as I was doing that, my son, Lucas walked in and he’s four and he listened to it with me and then he said, “Well, let’s do another one” and YouTube has those little sidebar things that you hope are decent and sure enough there were several options there and we started clicking on them and we probably listened to, at that moment, just five or six poems and he really enjoyed just hearing the poems read sometimes by the poet himself. We listened to some by Robert Frost and some by Billy Collins and there were some others. There’s a little bit of screening you’re going to want to do there because sometimes people will post, kind of, silly- just the way they posted on there, it’s more ironic the video they do instead of actually enjoying the poetry. But any time you can get the video or audio of a poet reading his own stuff I’ve found to be really neat, or somebody else reading the poem really well.<br />

Pam: So, it’s kind of like a poetry slam there at the house?<br />

Nicholas: It was fun. We haven’t done that much but it was just a couple of days ago that we did it, and he’s asked me a couple of times since then, “Can we watch more poems?” “Sure, that’s really cool.” And I use that as a jumping off point with him to say, kind of an intrinsic reward, well, we’ll keep listening but when you find one that you really like, we’re going to start working on that one, we’re going to memorize it ourselves. He listened to Casey at the Bat which is a bit too- he could do it but it’s a bit long right now. There were several that we listened to that I thought would be nice even Carl Sanburg’s The Fog Creeps on Little Cat Feet which is about six lines long and he enjoyed that. I’ve been thinking it could be a really good way to get him to do more of the same to mimic what he sees there and memorize some poems himself.<br />

Pam: What role do you think memorization plays in enjoying poetry?<br />

Nicholas: Oh tremendous, for a couple of reasons. There’s nothing like replaying these and again, I keep coming back to music because it’s so musical as we all understand, just to keep coming back to these beautiful sounds, or really clever word combinations or great images and to be really replay those with specificity through our minds or even say them out loud. I can’t tell you from memorizing some poems and I’m just driving and maybe I’m weird but some people sing in the car, I guess, more spiritual people probably pray in the car, and I just recite some of these poems, and it really delights me. I think obviously the mental faculty of memorizing something and memorizing something that’s really good. The opportunity to share with other people is great. Sometimes poets they just say the right thing in the right way and it’s fitting to the circumstance and you can, for lack of a better word, really bless other people, benefit other people by sharing those words with them, so I think that’s a value in memorizing it. It’ll be something they’ll carry with them as they become writers themselves and they’ll have it in their minds just how words sound together, what the rhythm of words is like. There are probably others but that’s a handful of good reasons.<br />

Pam: I have found my good anthology and I’m ready to start doing some poetry with my children. Is there anything I should be doing before, during, and after reading this poem to help my kids enjoy and understand it better?<br />

Nicholas: Sure. Beforehand, find the poems that you like, and that’s what I emphasize in that workshop more than anything, is at least for starters don’t, out of some sense of obligation, feel like you have to subject yourself to some poem that you don’t like. Now, there may be a time to read it later, I’m not saying down with the poems that you don’t like because they may be really valuable and worthwhile, at least for the beginning, like we said earlier, there’s something out there for everybody; find poems that you like, that make you smile, that really delight you, or that really gets you thinking, or catches your attention for one reason or another. And I think with most things, if you’re sharing these poems that you found, that you have an interest in them, your kids are going to be much quicker to pick up on those and to enjoy those as opposed to saying, ‘OK, Rudyard Kipling’s If makes the top 10 list on everybody’s list so we’re going to memorize that one first.’ It’s a great poem but it may not resonate with you or with your kids or this particular time in your life, and hopefully it will later. So I would say beforehand just find the handful that you like. Maybe find some of those readings that you really like, someone who reads it really well. I’ll just slide in here real quick Librivox.org is a pretty good site that has a lot of audio recordings; they’re free, from works that are in the public domain. I’m going to plug one here- a guy name Allen Davidson Drake reads a poem, the Jabberwocky and he may have two different readings on there but he’s either a really good faker or he has a really, really thick (it must be a Bronx, I don’t know, I’m from the south so all Yankees sound alike to me) it’s just such a great reading. So finding things like that, I think. I’ve even had kids who memorized Jabberwocky; this very, very southern Alabama girl she actually read the Jabberwocky in his accent because she had listened to it so many times, so that was pretty hilarious. During, just encourage the kids to read it, to read the words themselves, ask them if they like it. I’ve found that to be really useful- what do you like about this poem? Get them to think about, other than it’s short, which is what most of my 7th grade boys would say, find that thing that you like (“well, I like the rhymes”) OK, that’s great, that’s enough for right now. And then afterwards, I’ve found myself and my older kids, again 7th graders, just saying ‘Rate the poem 1 to 5 and just tell me why you rate it that way.’ It gets them to think of it in relation to other poems they’ve read; in terms, “I liked it more than this one because of [that] or less than that one because of [that].”<br />

Pam: So then they’re making those comparisons.<br />

Nicholas: And I love that. I think later on the question could be “What do you think this means?” It’s not a bad question; it’s just a bad question to start with. It’s not the first question I’d ask after reading a poem because I’m not sure… I think we’ve all walked through art museums. Sometimes a particular room or a particular artist just takes your breath away and it’s completely separate from the message they’re communicating it’s just what they’re doing and how they’re doing it. I’ll liken it to watching a sunrise or a sunset. I’ve never sat there at a sunset and explained to my kid, “Well, son, the way the sun’s refracting through the dust particles in the air is what’s causing that streak right there.” We don’t do that. We just go, “Ah, beautiful. Wow!” And I think sometimes that exalts the Creator of that sunset. We see beetles outside and sometimes inside and we marvel at those things. Maybe later on the understanding of what makes a beetle work or makes grass grow may be a worthwhile conversation and helps us appreciate the beetle more and the grass more and the lizard, or whatever it is. But it’s very seldom where we start with anything else, so that’s just my little plug there about poems. Start in the right place and just delight in the poem and the beauty of the poem itself and what’s delightful and good. That usually resonates with us anyway.<br />

Pam: Can you help give me a little cheat sheet? If it’s been a number of years since I’ve done any kind of literature and I’m reading these poems with my children and I know that in there, there are some devices, some different kinds of language that’s going on, could you just help give me a little cheat sheet of some things that I might look for?<br />

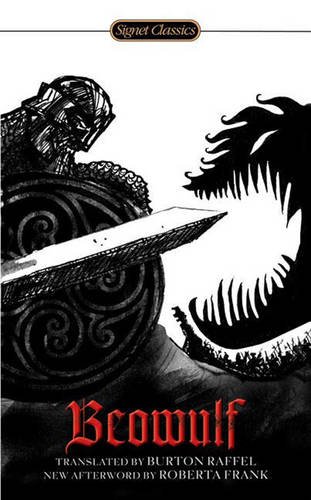

Nicholas: Before I give you my cheat sheet I’m going to give you Suzanne Clark who wrote a very helpful book called, The Roar on the Other Side. It’s a very practical book for writing poetry and for getting students/kids to write poetry and also for teaching a lot of the elements that are in there. It’s not a very big book; it’s put out by Cannon Press. I’ve found it really useful when I’ve taught some kids of varying ages several years ago, kind of an extended poetry workshop, so I do recommend Suzanne Clark’s book, The Roar on the Other Side. It also has a lot of really great poems in it. She has a good appendix with a whole bunch of poems in there that are a good starting place. What do you listen for? I’d start (because my favorite poet is Hopkins) with alliteration because he does that really well. That’s the repetition of consonant sounds or sounds at the beginnings of words. It’s not rhyming when he says, “The world is charged with a grandeur of God, it will flame out like shining from shook foil.” You get a sense of those first sounds: shining, shook, foil, grandeur, and God. So that’s all alliteration, and that’s probably the most playful device that we have, when you’re really going to have fun with words, and maybe other people besides me and some of my friends have done this where we’ve purposely when we’re talking try to alliterate as much as we can and giggle about it a little bit, and you say things in a funny way. So that’s big if you’re ever reading Anglo-Saxon poetry like Beowulf. A good translation of that will maintain the alliteration was really important. They alliterated instead of rhyming. Rhyming was brought in by basically the French. I didn’t say that with disgust on purpose, but Beowulf is a good example. If you read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which is a medieval poem after the Norman Conquest (William the Conqueror), then you see that it has both the English acts in alliteration very strong in it, but it also has a very strong rhyming element so you see those two things come in together. Those are both fun. So obviously the second one will be rhyming and most of us know how to do that and know what that looks like. It can be done really well or it can be done really poorly, obviously, and we can see something really childish rhymes, if they’re real, real hard rhymes at the end of lines, but they’re more fun when they’re worked into the middle of a line, you can see that, or when the line doesn’t stop at the end, there’s no punctuation that stops it so the rhyme, sort of, gets lost in the flow of the language. It’s neat sometimes to go back and re-read a poem carefully and realize it was rhyming a whole lot more than you thought it was. And I will say those are two rhyming certainly, it’s almost out noted. I don’t know that many poets today consistently write with any kind of rhyme scheme, like a regular rhyming plan at the end of every other line or every line or whatever, there was kind of a move in the, we were talking about the moderns that we were talking about earlier and a little before then, but certainly with the modern age where they were trying to throw off some of the standards and forms and we were just saying they were called more free. Some people have done it before then but in terms of valuable to them they basically said that rhyming became a whole lot less valuable in poetry and they wanted to write something that was totally free, so you still get people like William Carlos Williams who writes that famous poem, The Red Wheelbarrow: so much depends upon a red wheelbarrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens. And that’s the end of the poem. Not much rhyming in there, not much of anything that we’ve been talking about and yet it’s considered a good poem and I would concur, for what that’s worth. So that’s something- images. So we’ve gone from sounds (alliteration and rhyming, now to the things like images. So what are the visual things that happen when you’re reading a poem? And that can happen through sound. Again, like that Hopkins example, ‘it will flame out like shining from shook foil’ that’s a resplendor line, you see light shining all over that thing and reflecting off of it. But then we get other images and there’s some great Scriptural ones too, ‘your wound is incurable’ is part of Isaiah, ‘you’re sick from head to foot’ or we get ‘all of our righteous works are filthy rags’ those are really strong images. Another one is the Proverb ‘as a dog returns to his vomit so a man returns to his sin.’ I didn’t mean to pick three negative examples but we get these strong images that should illicit some kind of emotional gut response.<br />

Pam: So these are the pictures that we’re seeing in our head in response to the words that we’re reading on the page.<br />

Nicholas: Absolutely. And again, that can be elicited either through the word itself or even through the sound of the word. One of Suzanne Clarke’s exercises she uses in the Roar on the Other Side, one of my favorite poetic exercises, is she draws two shapes and real quickly, one of them is like a glob. Real rounded edges, and the other one has real sharp edges, a lot of pokies. And she says that one of these is named Una and one of these is named Keepik, which is which? That’s the only problem she gives you. It’s almost 100% (unless someone’s trying to mess with you) they always make Una the real flowy one and Keepik the real sharp one. Well, why? Why would it be? And yet, we all know that Una sounds round. Well, what do you mean it sounds round? How could something sound round? Round is a shape. It just has that sort of feel to it. The word has a feeling? It’s really fun to do an exercise like that with the kids, and then you keep on going and you say one’s a snare drum and one’s a tuba, one’s a lemon and one’s a melon, and so there’s some fun stuff to do with exercises like that, but it’s amazing what our brains do with a sound and how sensory a sound or a word can actually be.<br />

Pam: That’s really interesting. I went to a workshop a few years ago with Michael Clay Thompson (Michael Clay Thompson Language Art) he was talking about Shakespeare and how the witches in Macbeth and they’re using all of these d’s and g’s in these real guttural consonants in their speech but then you have someone like Romeo in Romeo and Juliet and he’s using softer sounds, he’s using these s’s and these round vowels sounds in his speech, and it was totally done on purpose. It’s amazing to think about how poets manipulate sounds in such a manner to make either these round soft images in our brain or these guttural sharp images in our brain.<br />

Nicholas: That’s just the incredible thing about the way that language works and the way that our minds work and I’ve not read extensive studies but it’s fairly universal some sounds just always illicit the same reaction from people in any culture no matter where you are, and that’s pretty fascinating too, but that’s probably another conversation.<br />

Pam: So we have alliteration and rhyme and we just talked about the images. Do you have anything else for us?<br />

Nicholas: There’s meter, which is again, how they string the syllables, the accent and syllables of the word together, and so most poetry and most spoken word is in something called iambic. We tend to speak alternating and in a poem you look at the general trend. If you look at the stress syllables you’ll see how they typically fall, so in Robert Frost’s famous poem ‘two roads diverged in the yellow wood’ we don’t read it like that “two roads … diverged … in the yellow wood” but we do read it like that, in a less accented way. Most of what Shakespeare wrote was in iambic, and usually what they call iambic pentameter, these are big words just meaning iambic has that same stress pretty much throughout the line and then the meters or the pentameter is how many of those iam’s there are. So if they’re five of them that’s pentameter, four would be tritameter, and three would be trimeter for a really short line of poetry.<br />

Pam: So I think before we lose people, one of the things that is like most things are kind of in this iambic flow but I think one of the things that our ear probably tends to pick up is when that’s broken.<br />

Nicholas: Yes, well said. And so, what a poet’s going to do is they’re going to try to jar you with a little bit. I wish I could just think of an example right off the top of my head of something that I just knew but I can’t. Give me five minutes after we’ve finished talking and I’ll probably have three or four examples. So they’ll jar you, or they’ll change it on you and normally what’s going on there is they’re usually trying to get your attention or emphasize something that, again, that’s communicated not with words and that’s probably the magnificent poetry in prose, good prose, which can be just as beautiful as poetry. In fact, another way I learned to love poetry was by reading the prose of Annie Dillard, one of my favorite authors, and she writes no poetry but her prose is just beautiful. It’s so poetic it got me reading a lot more poetry. A poet, because he just has more tools in his bag than a prose writer can do things, and like I said, I wish I had something right off the top of my head to give you there.<br />

Pam: I kind of put you on the spot.<br />

Nicholas: Give me a second and we’ll come back to that.<br />

Pam: In just that idea that, like you said, to get your attention, we’re doing something different here, this is the bad guy, or there’s some kind of disharmony that we’re expressing or something, something out of the ordinary …<br />

Nicholas: OK, can I give you one?<br />

Pam: Sure.<br />

Nicholas: So you think about Gerard Manley Hopkins, I’ll return to him and I cannot recommend him enough – if you were trapped on a desert island with only one complete collection of poetry it would have to be Gerard Manley Hopkins, especially if you’re a Believer, it helps. If you’re not a Believer it’s OK too, you’ll really like him. He was a Jesuit priest, actually. Just a brilliant guy, lived a very short life, but wrote some pretty world changing stuff and in a way ushered in what we know as modern poetry, and he died in 1895, so he has this poem talking about how fleeting beauty is, nothing can keep beauty at all. He ends the first part which is called the leaden echo with this very despairing (and you’ll see in a minute what I’m talking about) but the second part of the poem that butts up against it is called the golden echo and it begins to take a more hopeful tone. He says, ‘be beginning; since, no, nothing can be done to keep at bay age, and age’s evils, hoar hair, ruck and wrinkle, drooping, dying, death’s worst, tombs and worms and tumbling to decay;’ and then he goes on, he says, ‘so be beginning, to despair, to despair, despair, despair, despair, despair, Spare! There is one, here I have one (Hush there!); only not within seeing of the sun,’ and so what he does in that little moment there, where he says, ‘despair, despair, despair, despair, spare!’ something happens in our ear hopefully when we hear that as we train our ears to hear, we’re like, “Whoa” something’s happening, he missed something or something changed on me. So he goes from the word despair to spare (which means wait, stop, don’t despair for just a minute). Just the way he does that and that was the first thing that triggered, that really got my attention in that poem when I first heard it that just really fascinated me. It made me want to really immerse myself in that poem too.<br />

Pam: And so you don’t even have to be aware of where the stresses and unstressed syllables are in there to know that he’s done something different to get your attention?<br />

Nicholas: And then when they get your attention that’s the point at which maybe you can say, ‘Why did he do that? Is he having a bad day?’ No! He wasn’t having a bad day; they didn’t publish whatever came off their pen back in those days like we do now. It’s good and they did it for a reason. If you’re reading good poets then you dig deeper. That’s why I say we start with the wonder. We start with delight. And if we stop there, we may be OK. There’s a danger in that of course if you have someone with a very, very different world and life view than you who’s delighting you and you don’t stop to think about why, that could be dangerous. But there were a lot of shows on TV that would delight my son and I’m sure they would but I don’t want him to watch them because there’s something behind them, too, that’s insidious, that’s bad for him. Or junk food, a lot of us delight in junk food so not everything that delights us is good, but let’s that be the starting place to where we can say, ‘Let me find out it’s beautiful, is it true? Does it ring true? There is a message behind what he’s saying.’ And there are exceptions. Is there a message behind Jabberwocky? Somewhat, yes, and I think that’s a good one. It’s just a little quest- someone going out to find some kind of monster that apparently is terrorizing folks. If that’s as far as you get in the message of it then you’re probably doing pretty well. Train your ear to hear what’s going on and then again, let that be the thing that drives you to a deeper inquiry. And I believe your delight will increase than decrease at that point, the more you learn and study up on that poem.<br />

Pam: And I like what you say there- to train your ear. So you’re not saying open up all of these books about how to study poetry and read through them and figure out all of these different questions you need to ask and methods you need to use for studying poetry. You’re simply saying train your ear. Read and enjoy poem after poem after poem, and after a while you’re going to start hearing these things and picking up on them without having to slog through the big poetry for dummies or how to read poetry or anything like that.<br />

Nicholas: That’s exactly what I’m saying. And in fact, I’m saying if you want to NOT love poetry then open up the big textbook first. It’s almost tried and true, it’s unlikely that your return on that other thing is going to be very low than versus – and again, poetry is so easy to compare to other sensory things that we do- eating, or listening to music, or looking at nature or creation. There’s so much poetry and it’s just noticing what’s out there. And so, I think the training of the ear. I have a friend who’s a bird watcher, and he came to visit and we went out of his place one morning and we were out of the truck for, it was under a minute, and he said, ‘oh we’re going to hear some nut hatches today, and there’s a heron out here, and I’m really looking forward to seeing… we may even see a kingfisher, and he listed 10 or 12 different birds that we were going to see later, because he had a trained ear, he knew what he was looking for. I guarantee that began because birds delighted him at some point and then he started going in and going deeper. He did not just download an app with a bunch of bird songs on it and memorize all those things so that maybe one day he could make good use of it and impress his friend (which he did!) but I think the same thing here, just go to the tried and true – the good poets. It’s not hard to figure out who those guys are and immerse yourself in them and then you’ll learn what good music sounds like, you’ll learn what a good poem sounds like. Or you’ll eat at fine restaurants and know what good food tastes like and McDonald’s won’t be able to lie to you anymore because you’ll say this isn’t good (maybe it’s good at what it is- the dollar menu but it’s not good, it’s passable). So that training is so important.<br />

Pam: Help me out a little bit. Now, you’ve given me one anthology and that was A Child’s Anthology of Poetry. Do you have any others to recommend- any great poems, poets, or anthologies that we could list for our listeners?<br />

Nicholas: Yes, I could name a few. For our audience one of the great anthologies is, it’s pretty big (probably a couple of hundred poems in there) that’s the Child’s Anthology, and I’ve already recommended the Road on the Other Side which is both instructional and it has a great collection of poems all the way through it, so that’s something else I would definitely recommend. If you’re trying to get students (children) into poetry this has got to be one that you put in your arsenal. Luci Shaw, who I mentioned earlier, she was a good friend of Madeleine L’Engel who wrote, A Swiftly Tilting Planet. She wrote another one but I’m blanking on it right now.<br />

Pam: Me too. I know I should know it.<br />

Nicholas: Anyway, Luci Shaw is a friend of hers and Luci Shaw, I guess still is teaching up at Regent College up in Vancouver, she’s a poet herself but was also an editor for a collection of poems called, A Widening Light and the subtitle on that is Poems of the Incarnation. I find I pick this up usually around Christmas and Easter time and just find some really great poets written some really great stuff written around the person of Christ, from birth to death. I’d recommend Gerard Manley Hopkins, The Complete Works, that’d be a good place to start, or anything by Hopkins would also be fine. Then Billy Collins, a good way to start with Billy Collins is Sailing Alone Around the Room which mostly a collection of stuff from previous works and then a few new poems by Billy Collins and so that’s great. I’m trying to think of what else I may have had good luck with. Those should all get you off on a good start. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend a Norton Anthology necessarily. It’s got good poems but that’s usually written for a more academic audience so they’re picking “important” poems that are particular favorable in academia. They wouldn’t be my first pick, to get a Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry or Norton Anthology of Black Poetry or things like that. So, those are a few suggestions.<br />

Pam: Well, Nicholas, thank you so much for joining us here today and talking to us a little more about how we can enjoy poetry without fear, without being intimidated by it.<br />

Nicholas: It’s been a pleasure. Relax and enjoy some good poems.<br />

Pam: Thank you.<br />

For our Basket Bonus this week we have a fun cheat sheet of poetry terms for you. So, like Nicholas said in the podcast, you definitely want to start your study of poetry with wonder and focusing on the poems that you enjoy and simply enjoying those poems, but when you’re ready to take it a few steps further we have a downloadable cheat sheet for you of some of the poetry terms that Nicholas and I chatted about in the podcast and a little definition for each one, so you can print this out, put it in your Morning Time binder and have it there to refer to when you’re ready to ask your kids some more questions about poetry. You can find this at the Show Notes for this episode at EDSnapshots.com/YMB8. And those Show Notes are a great place to find links to all of the resources, books, and other things that Nicholas and I chatted about today on the podcast, so head on over there and check those out for all of the information that you need. And if you are one of the wonderful people who have left a rating or review in iTunes for Your Morning Basket I just want to say thank you so much, I really appreciate you doing that. If you would like to leave a rating or review you can find out how to do that on the Show Notes as well. So, EDSnapshots.com/YMB8, and I’ll see you guys again in a couple of weeks with another great podcast. And until then, keep enjoying Truth, Goodness, and Beauty with your children every single day.</p>

Links and Resources from Today’s Show

- A Child’s Anthology of Poetry compiled by Elizabeth Sword

- The Roar on the Other Side by Suzanne Rhodes

- Sailing Alone Around the Room by Billy Collins

- Gerard Manley Hopkins: The Complete Poems

- A Widening Light: Poems of the Incarnation by Luci Shaw

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- Beowulf

- Links to Poetry Foundation for many of the poets and poems (including some audio) Nicholas mentioned:

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Billy Collins

- Robert Louis Stevenson

- Lewis Carroll

- Ogden Nash

- Rudyard Kipling

- Hilaire Belloc

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Robert Frost

- “Casey at the Bat” by Ernest Lawrence Thayer

- “The Cremation of Sam McGee” by Robert Service

- “Fog” by Carl Sandburg

- “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams

- Librivox recordings of “Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carroll

Key Ideas about Poetry

- Poetry is part of being human.

- Poetry is something to be experienced and enjoyed, not just mastered.

- “What do you think it means?” is not a bad question, but it is not the first question you should ask about a poem.

- Train your ear to delight in poetry by reading beautiful poems, especially those with truth behind them. Just keep reading.

Find What you Want to Hear

- 2:00 the importance of poetry; poetry in Scripture; the innate desire to express experiences and emotions through song, poetry, and analogy

- 3:58 We don’t necessarily have to understand poetry to first enjoy it.

- 6:02 using poems you like to branch out to other poems

- 7:19 finding excellent poetry that resonates with children but is not childish

- 9:40 poetry recommendations for beginners

- 11:40 ways to enjoy poetry together as a family

- 14:06 the role of memorization in enjoying poetry

- 15:41 the importance of first finding poems that resonate with you

- 17:38 questions to ask about poems

- 19:39 literary devices to look for in poetry

- 32:31 starting with wonder and delight; training the ear to love beautiful poems

- 36:26 more recommendation of great poets, poems, and collections about art

- 26:49 encouragement for mothers intimidated by teaching art

Pin

PinLeave a Rating or Review

Doing so helps me get the word out about the podcast. iTunes bases their search results on positive ratings, so it really is a blessing — and it’s easy!

- Click on this link to go to the podcast main page.

- Click on Listen on Apple Podcasts under the podcast name.

- Once your iTunes has launched and you are on the podcast page, click on Ratings and Review under the podcast name. There you can leave either or both!